Before the dawn of agriculture 10,000 years ago, if you wanted to eat, you had to forage for your food.

Hunting and gathering was our first and most successful adaptation as a species, a strategy that shaped more than 90 per cent of human history.

Industry and agriculture dominate more recent times, and the hunter-gatherer model is a dying way of life.

However, as we take our first steps into autumn, past hedgerows thick with berries and fields rich with mushrooms, it is comforting to know that the art of how to forage is alive and well.

Geoff Dann, a Sussex-based foraging expert and instructor, says interest in the art is growing fast.

“Foraging, especially foraging for fungi, has never been more popular in Britain, and interest is rapidly growing,” he says.

“There are two main reasons. The first is a widespread food revolution. We now have a massive diversity of restaurants serving food from all around the world. Pubs have become gastro-pubs and cookery competitions dominate prime-time television.

“It’s no surprise that the foodies among us are taking a greater interest in the possibility of finding, fresh and for free, delicacies that cost a small fortune and are often only available dried – if you can buy them at all.

“The other strand is a broad cultural trend towards sustainability, self-sufficiency and a desire to reconnect with the landscape and the natural world.

“There is a sense that our civilisation is heading towards catastrophe, both economic and ecological. And we’ve responded with a desire to re-learn ancient and forgotten skills. Foraging for wild food fits very well into this cultural backdrop.”

Though he also hunts for berries, nuts and other wild food, Geoff specialises in fungi hunting. A former software engineer, mycology has been a hobby of his for almost 30 years.

After a childhood spent roaming the Surrey Downs, and an interest in nature piqued by David Attenborough’s ‘Life on Earth’, Geoff taught himself about mushrooms as a teenager.

He explains: “Foraging for fungi became my hobby, and I would go out two or three times most autumns and learn something every time.”

After he was made redundant after 15 years as a software programmer in 2004, Geoff decided to use the freedom afforded by the absence of commitments and the equity in his Brighton home to pursue his passions.

After gaining a university degree in philosophy at Sussex University, and dabbling in a series of part-time jobs, Geoff’s hobby, by chance, turned into a job.

“Late in the summer of 2009, with time on my hands, I set myself the task of systematically searching Sussex for every species of edible, poisonous or common fungus that I couldn’t remember having found and identified,” he says.

“I also did this just because I wanted to. It wasn’t intended as a career move. It just so happened that a close friend of mine was also made redundant around that time, and was more than happy to accompany me on some of my walks that autumn.

“He provided me with my first experience of teaching somebody else about foraging for fungi, and he also alerted to me to the growing interest in the UK in foraging for other things.

“With the explosion of interest in this country, about five years ago people started asking me to teach them. Now I do it full time every autumn.

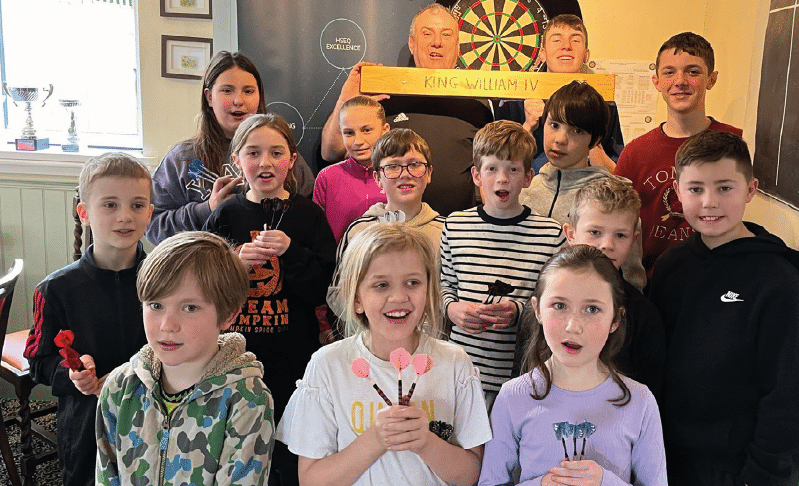

“It’s mainly groups of friends, families, colleagues or chefs who hire me. I’ll take them for a walk somewhere and teach them about all the mushrooms we find along the way, with them taking home any mushrooms that they want.”

As many mushrooms are toxic to humans, if you do go out hunting this autumn and intend to take your harvest home, Geoff says it is vital you know what you are doing.

“There are six or seven times more species of fungi in the UK than there are plants,” he explains. Even if you have a book with 1,200 species in it like Roger Phillips’ Mushrooms, you will still come across stuff that isn’t in the book.

“And wishful thinking is a problem. If you find something that looks vaguely like what you’re looking for, the tendency is to think you’ve found what you want to find.”

To overcome the perils of nature, and human nature, Geoff recommends caution and education.

He says: “There is one species responsible for every single mushroom-related death in the UK since the advent of modern medicine, and that’s the death cap.

“Unless it matches the image and description of what you’re looking for exactly, don’t eat it. And learn the poisonous ones first. There are only a handful of deadly ones, but it’s amazing how many people don’t know which they are.”

Though foraging now provides an income for Geoff, excitement and enjoyment are what drive him to continue.

He said: “What really keeps me going is not knowing what’s around the next corner. I’ll sometimes walk for miles without finding anything of interest.

“Other times I’ll find the real delicacy or something I’ve been looking for for 30 years and never seen before.”

But if you want Geoff to tell you where to look for such rarities, you might be disappointed.

He says: “One of the first rules of foraging is not to give away the best locations of where to find things. If you do, everyone will go there and there’ll be nothing left.”

He will share the rest of his extensive knowledge though. Geoff is penning a book, scheduled for publication next autumn, which he says will ‘set a new standard for British fungi foraging.’

The book will provide detailed information and high quality photographs of about 300 of the most important edible, toxic and common species, plus a few that are of interest for other reasons.

If you can’t wait until next autumn to go hunting, find an expert like Geoff, and safely experience the magic of mushrooms.

FUN FUNGI FACTS:

? Long before trees overtook the planet, Earth was covered with giant mushrooms, up to 24 feet tall and three feet wide.

? Mushrooms are more closely related to animals than humans. They are now classi? ed in the same superkingdom, Opisthokonta.

? Mushrooms, along with bacteria, are responsible for the recycling that returns dead matter to the soil in reusable form. Without fungi, we would be covered by a thick layer of dead plant and animal remains.

? Mushroom spores are made of chitin, the hardest naturally formed substance on Earth.

? Mushroom rings that circle Stone Henge

are some of the oldest colonies on earth. The glowing rings are so large they are best seen from airplanes.

? A Mushroom fossil dating back more than 420 million years was discovered in 1859.

? The ‘honey mushroom’ in Oregon is the largest living organism on the planet. The 2,400 years old giant covers 2,200 acres.