As ceremonies were held across the region to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Battle of the Somme last Friday, 12 members of one Tunbridge Wells family travelled to the battlefield in France to remember the heroic part played by their ancestor, Lieutenant Frank Thornely.

At the age of 19, Lt Thornely led a famous charge by the 11th battalion of the Ulster Division on the Schwaben Redoubt at Thiepval on July 1 1916.

The action was immortalised in a painting by James Princep Beadle entitled Attack of the Ulster Division, which hangs in the City Hall in Belfast.

Celia Preston, Lt Thornely’s daughter who lives in Eridge Park, made the trip to Thiepval with her brother Nick, five grandchildren and five great grandchildren. Last Friday they were official guests at a remembrance ceremony at the Ulster Memorial Tower – the first monument to be erected on the Western Front in 1921.

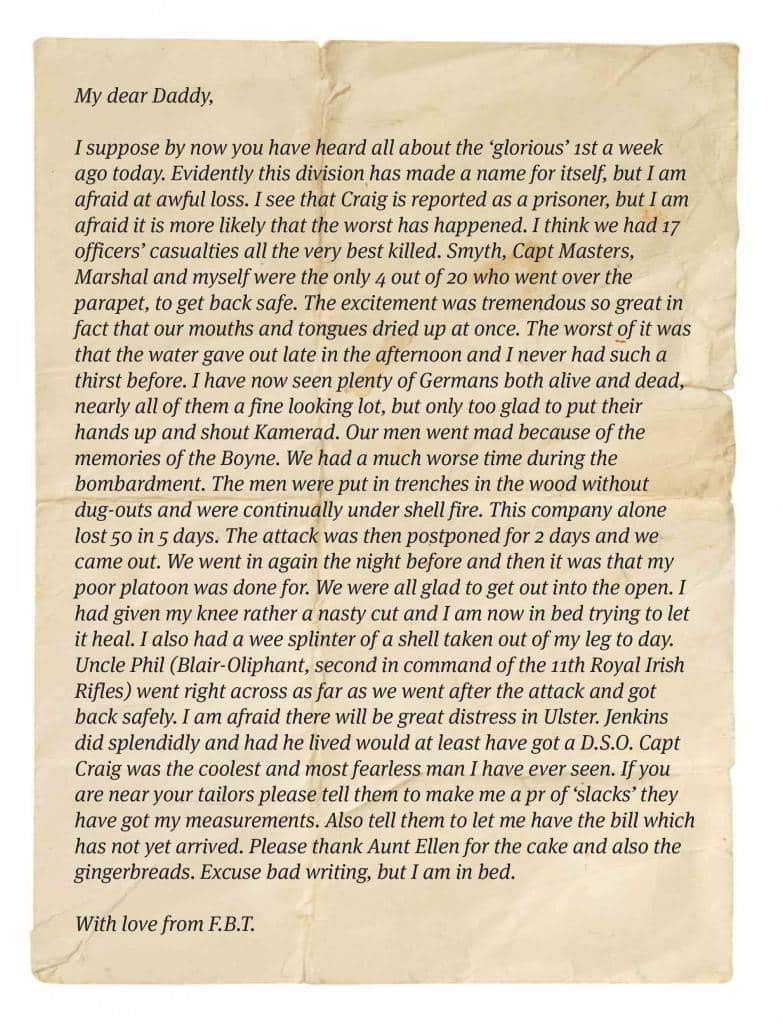

A letter (see below) from Lt Thornely to his father was read out at the start of the service, with Prince Charles, the Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby and the Northern Irish First Minister Arlene Foster in attendance.

Mrs Preston, 78, said: “I wanted to walk in the footsteps of my father from the trenches to Schwaben Redoubt. It’s amazing he survived.

“He was one of the few to get to his objective on that first day. And he described how on the way back he was stepping on all the dead bodies.”

Lt Thornely was one of four officers out of 20 who was not killed or injured in the assault on one of the German army’s strongest positions.

She visited the site for the first time with her father in 1947. “It was very moving, he wanted to go back and show us the most important thing that happened to him in his life.

“I was nine, and very aware of everything. My father paced it out, he was enraptured at returning. He told us his feet didn’t touch the ground and we didn’t realise what he meant until he said he couldn’t put his feet between the dead bodies.”

“He was a captain at 19, and he actually lived in a certain amount of comfort. He told us how he took over a German dugout that had been beautifully lined with wood, like a grand room.

Educated at Uppingham School, that fateful day was his first engagement. “He was always a happy man, I suppose he considered himself to be so lucky,” said Mrs Preston.

“He kept up with his friends from the division. Many were gassed and went blind. He visited one of them in the evening, and found him pruning his roses in the dark because he couldn’t see.

“He died at the age of 62 – very young. He loved his sport, he was a great cricketer and horseman. He had a horse behind the lines, which was killed under him when a shell exploded next to him.”

The battalion of the 36th Ulster Division were the only troops to reach the German second line on that first day, when 19,240 British soldiers were massacred. They avoided getting caught up in the bloodbath because they used a ‘much cleverer tactic’, according to Lt Thornely’s grandson Adam.

“Most of the troops went over at 7.30am when the seven-day bombardment of the Germans ended,” he said. “They just walked over no man’s land. That was a horrible miscalculation.

“The shelling had not reached the German lines. They thought they would find the trenches empty but the enemy was waiting. They mowed them down.

“There were huge numbers of amateur soldiers, the ‘Pals Battalions’ as they were known, and they were given simple, precise instructions. So they just carried on walking.”

“But Frank’s battalion had crawled into no man’s land before the rest went over the top and they rushed forward as soon as the shelling stopped.”

So quick were they in reaching the German defences that there were many casualties caused by British shelling.

The first day of the Battle of the Somme saw a total of 57,470 British (and Irish) casualties, equivalent to the population of Tunbridge Wells.

The attack by the 11th battalion that day was emblematic of the sheer futility of a battle which would last for almost five months.

Lt Thornely’s troops were exposed on three sides at Schwaben because of the failure of the other attacks, and were ordered to pull back and give up all the land they had gained.

He was awarded the Military Cross for his actions and worked closely with the artist Beadle while on leave, sitting for his portrait and providing detailed information.

The image was featured on a stamp 10 years ago as the Irish government honoured for the first time its citizens who fought in World War One.

He also wrote hundreds of letters to his parents – always separate, and with very different content – from 1914 until the Armistice, which have been preserved by the Somme Heritage Centre in Northern Ireland.

“It was an unreal combination of horror and camaraderie,” says Adam. “At one stage he writes: ‘I’m so glad of all that cricket practice because it’s made me a great bomber’ – that’s what they called lobbing grenades.”

Lt Thornely went to India after the war but returned to Britain in 1944 to take up a post with the War Office. He settled in Goudhurst and then Frant Road in Tunbridge Wells. Celia now runs a bed and breakfast at Deer Cottage on Bunny Lane.

141 DAYS IN HELL

- July 1 1916 to November 18 1916 (141 days).

- Estimated casualties on the first day: 57,470, of which 19,240 died – the bloodiest day in the history of the British army.

- Allied estimates at the Chantilly Conference on November 15 1916: 485,000 British and French casualties, 630,000 German.

- Later figures suggest 419,654 British casualties. French official figures state 202,577. German losses are disputed, ranging from 400,000 to 680,000.

- More than a million men were wounded or killed, as the Allies pushed the German lines back by six miles.

- The Lochnagar mine was detonated under the Schwaben Redoubt at 7.28am on July 1, two minutes before the troops went over the top.

- It was loaded with 60,000lb of Ammonal, in two charges of 36,000lb and 24,000lb.

- It produced a crater 450ft across. The soil was lifted some 4,000ft into the air in the first blast.